Grail Structure and its Purpose in The Waste Land

|

The Waste Land is a sadly apt title for the destruction that was left of Europe after the First World War. Great cities were destroyed in aerial attacks and trench warfare left desolate stretches of land all throughout the countries involved. The new, modern conflict left people questioning whether it had all been worth the effort. One soldier published Nothing of Importance: A Record of Eight Months at the Front in 1917 (Trott). People were disillusioned with their lives, their governments, and a humanity that had come to the point of accepting such gross fighting. They no longer had the same whole-hearted appreciation of technology after watching as new weaponry ended countless lives in mere heartbeats (Templeton, 530). They needed something that they could believe in again—something that would give life a higher purpose than just so much death and cruelty.

|

As an interesting sort of twist of legends and responsibility, Eliot assigned blame to the Fisher King for the sickness of the kingdom only once in the poem, drawing heavy parallels between the state of the waste land and scenery from the trenches of World War One. He writes, "Musing upon the king my brother's wreck, and on the king my father's death before him. White bodies naked on the low damp ground and bones cast in a little low dry garret, rattled by the rat's foot only, year to year," (Eliot, lines 191-195). In the narrators eyes, the King and his sickness—which has become the sickness of the land and its people—are responsible for the fall of his brother and father. Their dead bodies rot away, and their bones are improperly buried, simply lying uncovered on the dry, inhospitable earth. Scavengers crawl over them, taking away what little dignity unscathed dead bodies could have to begin with. This passage carries direct applications to the First World War. The narrator essentially blames the leader of his country for sending his father and brother off to fight in the trenches. Their bodies are stripped of all useful goods after they are killed in combat. They are left to decay on the "damp ground" or in "low dry garrets", with no one coming to find them so that they can be buried formally. Eliot explores the anguish and anger of survivors of the war, and how they were left to cope when many of their loved ones never came back—often blaming their governments for the devastation wrought on the land and its people. He uses the Fisher King and the waste land to paint a picture of the kind of hopeless desolation they felt after everything ended.

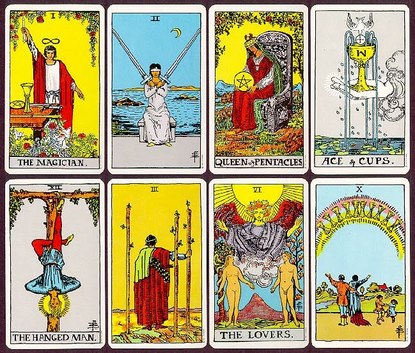

Another member of The Waste Land's cast is key to the structure of the Grail quest and the theme of reliance on mystical forces for recovery. She is Madame Sosostris, who reads tarot cards to determine the narrator's future. The tarot deck, like the usual deck of cards, has four suits. They are the Cup, the Lance, the Sword, and the Dish—the same four symbols are called the hallows of the Grail Castle, where the Holy Grail lies in wait protected by the Fisher King (Griffin, 77-94). They represent the pillars of the quest for the Grail. This tie that immediately suggests a bond between gypsy mysticism and the Grail quest has a deeper meaning still. Originally the symbolism of tarot cards has been connected to designs found on ancient Chinese and Egyptian monuments whose purposes were linked to the change in the water levels of great rivers (North, 36). This ties directly to the great theme of water in the poem, and the idea of water as being life-giving—to be discussed later.

Eliot uses destruction imagery in The Waste Land to symbolize the extent that countries were ravaged and sick after the war. The only way for him to accurately portray how Europe had been affected was to describe the barren lands of the Fisher King. Eliot writes, "Out of this stony rubbish, Son of man, You cannot say, or guess, for you know only A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, and the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, and the dry stone no sound of water," (lines 20-24). The "stony rubbish" he describes is the wreckage of great buildings, fallen after countless bombings. "Images" of the past—the perfect cities and homes that had been thriving pre-war—were smashed to bits along with the physical landscape. Even the memories of soldiers were scattered and broken as a result of trauma. The people were needy, but no one could help them. The governments of Europe post-war scrambled to pick up the pieces and promote diplomacy, and just didn't have the time to help all of their people recover. They were dead trees—they existed but could not provide relief. The people were in search of water, some great force that could lift them up from their misery and help them regain their vitality, but none was to be found in the rubble. The scenery of The Waste Land is powerful in that it shows how the fundamental needs of Europe's peoples were not being met—making their recovery slow and painful.

|

"Here is no water but only rock... If there were water we should stop and drink Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think... There is not even silence in the mountains But dry sterile thunder without rain If there were water And no rock If there were rock And also water And water A spring A pool among the rock... Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop But there is no water" (Eliot, lines 331-358) It is here that the landscape of the waste land is truly described—dry, sterile, and devoid of life. There is no water, no source of hope or clear road to recovery. Eliot makes sure that the description sounds harrowed and half-crazed. It is the rambling of someone who describes the desolation of the world around them and seeks a savior—the kind of hopelessness created by the mass destruction of the First World War. After the war, people had to look somewhere for help rebuilding their lives and lands. Eliot represents an appeal to a higher power through his poetry, invoking biblical scenes and a mysticism that reveres nature as unpredictable and all powerful. |

Water is one of the grand themes of the Grail quest and The Waste Land. In Grail legend, the river that feeds the Fisher King's lands dries when the King falls ill. This is part of what leads to the creation of the waste land. Nothing more is left to nourish the kingdom and keep it alive. The land needs its life blood, which is tied directly to the Holy Grail, as the river would fill once more if the Grail quest were to be completed. This would result in the kingdom healing and returning to its former glory. Eliot uses the theme of water all throughout the poem. He focuses on there being a lack of water, or on the existing water source of the narrator as being impure. Eliot writes, "Oed' und leer das Meer," or empty and desolate is the sea. The bodies of water available are not life-giving, and those that could revitalize the land are unreachable (as long as the Grail remains unreachable) (Pratt, 315). In the section "What the Thunder Said" a landscape is described in which water is sorrowfully absent.

In the end, Eliot weaves a picture of how the problems of the land must come to be solved. The Fisher King gives up his hope that someone will complete the quest for the Grail. The land is still "arid"—dry and lifeless around him, signifying that the healing waters have not returned. He decides to try to put the sad pieces of his kingdom back together anyways, hoping for the best. This is Eliot's rejection of the idea that a savior can be mystical and all-powerful. He looks pragmatically at the world and uses the Fisher King to tell England how it needs to heal itself. In Eliot's eyes, it comes down to putting back the pieces and trying to fit them together as well as possible, letting time heal the wounds. |

The wounded Fisher King

The wounded Fisher King

"I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

Quando fiam uti chelidon—O swallow swallow

Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih"

(Eliot, lines 423-433)

Eliot's final words, "Shantih Shantih Shantih," translate loosely to "The Peace which passeth understanding," (Rainey, 126). He ends his lamentation of the state of the world post-war with a call for a higher peace—and through this peace, recovery.